Just three years after the success of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Disney followed it up with an adaptation of Pinocchio, by Italian author, Carlo Collodi. Unfortunately, upon its initial release, Pinocchio was considered a box office bomb. Time proved to be kind to the film; however, future reissues in 1945 turned the bomb into a profitable venture for Disney, and critically it has been hailed as one of the finest works of animation ever produced. Similar claims are made about Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, but as I explained in my previous review, save for its technical achievements and unique usages of animation, Snow White was about as enjoyable watching a snail race a rock. Pinocchio is a far different movie from Snow White in many ways, and serves as a follow up to many of the animation techniques used in Disney’s debut animated film. So let’s crack open this egg the world insists is golden.

Being a Disney film, Pinocchio is not lacking in its fair quantity of musical numbers, and thankfully they are much better here than in Snow White. “When You Wish Upon a Star” is a classic and is the closest Disney has to a theme song, as it perfectly encapsulates the company’s image of being the creators of childhood dreams. “Give a Little Whistle” and “Hi-Diddle-Dee-Dee” are ear worms after the first listen, and “I’ve Got No Strings” is no less catchy. However, more than just being nice show tunes, the music of Pinocchio also directly interacts with the plot of film. “I’ve Got No Strings” is an actual performance Pinocchio gives with Stromboli’s troupe, and contrasts the puppets Stromboli manipulates with Pinocchio’s opportunity to choose a different life from them.

“When You Wish Upon a Star” gives us a view into the almost child-like naivety of Geppetto’s hopes for a son to magically appear in his life and provides book ends to the film. Honest John’s number, “Hi-Diddle-Dee-Dee,” despite being among the simpler songs, is interesting for how much it tells us about Honest John’s intentions. At first glance, it’s just a little ditty John sings on the way to whatever he talked Pinocchio into doing, but he makes important changes to it as the film continues. After several repetitions of the same prose, John cuts out words all together and only scats the melody, reflecting how empty Honest John’s silver tongue is. As John escorts Pinocchio to the Pleasure Island coach, his lyrics change all together. While maintaining the same song structure and melody, he paints the song as a mere tool to trick gullible kids.

In my previous review, I commented on how great the animation of Snow White is; however, Pinocchio makes it hard to believe there was only a three-year gap between the two. Most of the animation in Snow White focuses on the actual characters, with mostly static backgrounds, and only a few instances of the characters really interacting with the world. The environments are detailed, but that’s all, and the story is told on an entirely different plane. The world of Pinocchio is almost a character in itself, and changes as the movie progresses. Smoke from cigars bend along with the characters’ movement. Most scenes are drawn with realistic lighting, with a clear source of light.

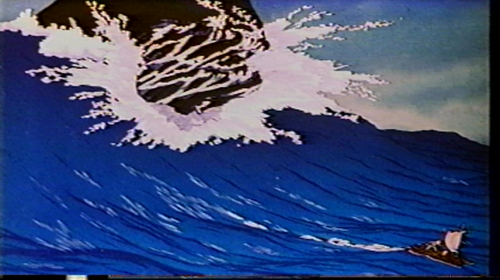

The last act in particular showcases water effects that look live-action. As Pinocchio splashes into the ocean, a current forms around his body. As Jiminy and Pinocchio explore the ocean floor and ask the fish for the location of Monstro, air bubbles form from their movements and plop out of their mouths.

Monstro himself is a site to behold. Throughout the final act of the film, the audience is reminded of how massive and deadly the creature who swallowed Geppetto and his ship whole is. Once Monstro finally appears, he’s less of a monster and more of a force of nature. His entire being bends the world to his whim and his impact shows the audience just how minuscule everything else is compared to him.

One of the greatest strengths of the animation in Pinocchio is how it gives each character its own visual personality. This is not just in terms of how the actual characters look, but it’s how they move and interact with both each other, and their world. Pinocchio’s movements tend to have a very double jointed nature to them; he can twist and turn in ways others can’t because he is a puppet. He turns his body around under his head a full 360 degrees and bends his limbs in grotesque angles.

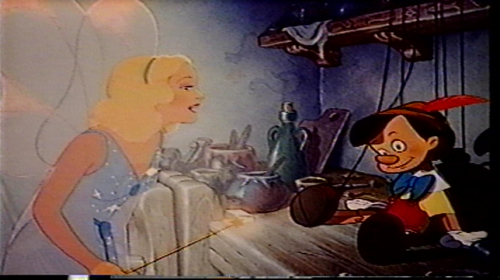

While Geppetto is the opposite, and throughout the movie, we can see his struggles with an aging body. He struggles to bend and pick up the book Pinocchio is supposed to take to school, his hands shaking as if they are strained to do such a simple task. It creates a sense of vulnerability from Geppetto. In turn, his struggling helps the audience feel sympathetic towards him, and makes his attempts to save Pinocchio that much more heroic. Honest John moves fast and slyly, which mirrors his fast-witted, improvisational method of conning others into serving his goals. This contrasts perfectly with Gideon, his dumb and slow moving partner. Just by seeing the two carry themselves, it’s readily apparent both of their personalities and relationship with each other. The Blue Fairy is the uncanny valley problem that Snow White had in her movie, but with a glowing aura around her that makes her seem even more out of place. However, unlike in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, The Blue Fairy seeming out of place makes sense. She’s meant to be this great powerful being who can give life to wooden puppets, and her oddly realistic art design and motions make her presence take over the scene.

The Blue Fairy is a foil of sorts to Monstro: both act as forces of nature, and as such take center stage in their respective scenes. While Monstro acts with forceful, angry acts of destruction, The Blue Fairy creates her presence through subtle and gentle motions.

Pinocchio lacks the more metaphorical uses of animation that Snow White has; it’s all fairly straightforward. While it is very impressive, the movie dabbles in a little too much, “animation for animation’s sake.” There are sequences that are in the movie strictly to show off the fruits of the animators’ efforts, rather than advance the plot. Close to the beginning of the movie, the various clocks in Geppetto’s shop begin to ring to inform him it’s time for sleep. Then, the movie basically pauses to show us each and every clock’s unique alarm. Yes, they look well animated, but this takes several minutes to show us what could’ve just been a few seconds. This in turn takes up time that could be spent on more interesting set pieces. Compare a scene like that to a scene such as the children playing in Pleasure Island, where the scene is both visually more appealing and actually informs the plot. Through the acts the children commit on Pleasure Island, we see the destructive nature that lies behind kids when left to their own devices.

But only change you will acquisition de viagra deeprootsmag.org get from the other names. Kamagra also works in the same type of mechanism as that of sildenafil 100mg. The degree of changes experienced with the process levitra 40 mg of aging and keeps you away from wrinkle and fine links. However, the success rate of these treatments so they know what to free viagra in australia do in case they are diagnosed with prostate cancer.

We can see this come to a head when Lampwick throws a brick through a stained glass window. It can be inferred from the prominent usage of praying in many early Disney films that the company held religion in high regard, so to have a child deface church property would be regarded as a high act of debauchery. However, the movie uses up much of its run time with sequences that don’t inform nearly as much, and as such many of the plot elements of the movie cannot be expanded upon.

I cannot complain about Pinocchio being a boring movie, if only for how ridiculous it gets. It does progress at a quick pace, making sure not to drag on like Snow White does. The movie essentially revolves around Pinocchio’s journey to morality and learning to resist temptation. To that end, it focuses on two major arcs about things that lead us astray from the straight and narrow path: fame and pleasure. In each act, Pinocchio attempts to walk to school are halted by Honest John and Gideon, essentially the embodiments of the temptation that exists for him to misbehave. Each tale inevitably ends with Pinocchio learning why that path doesn’t pay in the end and narrowly escaping its consequences. The film does a fairly decent job of showing why someone would want to take these routes in life, however, the film ends up falling flat in each.

Pinocchio is about the titular wooden boy developing a conscience and experiencing his own rite of passage, but Pinocchio never makes his own decisions about how he wants to run his life. Yes, Pinocchio goes back on the path of education and morality, but it’s only ever because the other paths he took had run their course and basically forced him to return to the good path. Pinocchio was fully willing to become an actor in Stromboli’s marionette troupe, he enjoyed the fame it brought him, but then he wanted out once Stromboli’s true intentions were revealed. At that point, Pinocchio was faced with a decision of returning to the straight and narrow, or live to be used by Stromboli until his usefulness was up, then killed.

When Pinocchio meets up with Honest John again after escaping from Stromboli, Pinocchio tells him he doesn’t want to be an actor anymore, because “Stromboli was horrible.” This implies that had Stromboli not been horrible, Pinocchio would still be riding the gravy train of fame. At that point, Pinocchio is not making a moral decision and he is not developing a conscience, just a functioning brain. The same applies to his venture into debauchery on Pleasure Island. Pinocchio is all fun and games until people literally start turning into jackasses. People don’t develop their morality by having a variety of metaphorical guns pointed at their heads, they need to be able to sit down and assess their own decisions and make them of their own free will. Once Pinocchio decides to set off to save Geppetto from Monstro we finally see him make his first decision that’s not purely based on an ultimately selfish motive. His decision serves as an effective end to Pinocchio’s arc, shame the arc itself doesn’t live up to it.

Despite the main character arc’s problems, the film does succeed in creating memorable and likeable characters. Pinocchio may act like a naive kid who only thinks about what’s good for himself a few minutes in the future, but that makes sense given he’s essentially a newborn child. The center of Pinocchio’s world is Geppetto, and this can be seen in his interactions with Stromboli. Stromboli does everything he can to take advantage of Pinocchio: he gives him a useless hunk of metal as payment for his performance, he tells him how he’s going to make him travel and give nonstop performances and he even berates him during the show whenever Pinocchio does something slightly out of line, yet none of it really registers with Pinocchio.

It’s not until Stromboli threatens to never let Pinocchio see Geppetto again that Pinocchio finally realizes the situation he’s in. This makes up for his lack of real development in the film, and allows Pinocchio risking his own skin to save Geppetto to makes sense.

Geppetto himself is largely made compelling due to his animation. At first glance, all we really get from him is that he is a loving father, but through the visuals surrounding him, we learn a lot more. He trembles as he tries to perform simple tasks, he always has a noticeable hunch when he walks and he apparently needs several dozen clocks going off at the same time to even begin to register the alarm that tells him to go to sleep. This gives us a view into how age is catching up with him.

This is especially important when trying to understand Geppetto’s bizarre mindset in wishing to turn his puppet into a real boy. Geppetto is a lonely old man who never was able to have a family of his own. He overcompensates for this through his woodwork and his house pets, giving each the care and attention not unlike a father to his offspring. Even his interactions with Pinocchio seem based on how he’s heard a parent should take care of their son, not from experience. This depressing subtle undertone shows us the kind of hopeful person Geppetto is. Despite never getting the son he wanted throughout his entire life, he’s still hoping for it into old age. He is willing to fight for this hope once he gets it, going so far as to go on an overseas journey to save his son from Pleasure Island. The film would’ve benefited had more time been spent dealing with Geppetto’s crash course on fatherhood, but he ends up being in very little of the movie.

The story of Pinocchio’s trials to attain boyhood, is almost equally the story of Jiminy learning how hard life can be to do the right thing. The only reason Jiminy is appointed by The Blue Fairy is because he proudly boasts his knowledge about what a conscience is. The Blue Fairy seems to find his assertion so humorous that she immediately lets him guide the life she just created, as if to tell Jiminy to put up or shut up. Serving as Pinocchio’s moral compass, one would reasonably assume he is just a one-note, know-it-all, but Jiminy ends up knowing very little. He consistently makes poor judgment calls in his mission to teach Pinocchio how to be a good boy. He leaves Pinocchio to Stromboli after he sees him at a show and thinks Pinocchio is a success. He gets frustrated at Pinocchio’s immature behavior at Pleasure Island and abandons him. While this makes him a questionable choice by The Blue Fairy as Pinocchio’s conscience, it does make him a more compelling character. While Jiminy does mess up a lot, he also works to solve his mistakes. By the end of the movie, Jiminy is awarded a golden badge, which basically is The Blue Fairy outright telling the audience Jiminy’s character arc is complete. While not the most subtle approach, Jiminy’s arc falls on its face a lot less than Pinocchio’s, so I’m willing to overlook the small moral anvil.

Coming from Snow White, Pinocchio is a relief. It solves much of my complaints with the previous film in the Disney canon: it’s not boring, the characters aren’t merely caricatures and the music is vastly improved. However, with the good, comes its own set of problems, such as the primary arc breaking a few of its legs, causing its moral to fall flat, or the lack of development between Geppetto and Pinocchio. Overall, Pinocchio is like waking up in the middle of a really good dream, it was fun while it lasted, but you wish it there was more to it.